jet_airplane <- paste0("F", c(16, 35, 18))

x_is_in_string <- str_detect(string="my string", pattern="x", negate=FALSE) # str_detect will return FALSEParsing R code

1 Variables, literals, functions and operators

Most of the R code you will be looking at, consists of:

- Variables

- Literals

- Functions (and Operators)

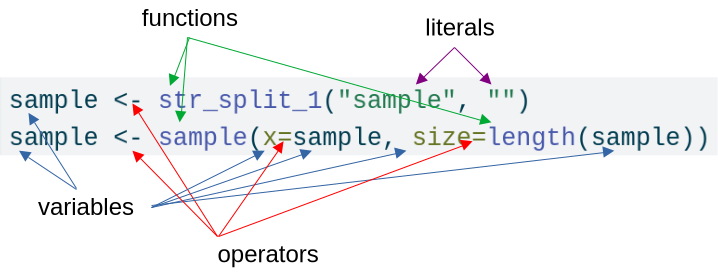

Reading and understanding R code (and spotting mistakes) is a lot easier, if you learn to distinguish these four elements from each other. Look at these two lines of simple R code (note how RStudio will help you by applying different text colors):

Quick explainer:

paste0()will paste the"F"and three numbers into a vector, so thatjet_airplanebecomes"F16" "F35" "F18". Another function,str_detect()will look for the pattern ("x") in the string ("my string"), so thatx_is_in_stringbecomesFALSE(as opposed toTRUE)

In the following, we over-simplify things a bit. For more details, return later to the subsection Self study / Core concepts / Variables. For now, read on to learn how to parse code with variables, literals and functions:

2 Variables

Variables are named references for data in memory. You can not work with data in memory, except through named references, i.e. variables.

In one sense, this is similar to the way you use file names to reference individual files on your computer: The name remains the same even if the content changes.

In the R code above, jet_airplane is a variable. We decided to name it jet_airplane at the time of writing this text – we could have called it (almost) anything else. x_is_in_string was also a discretionary choice of variable name.

Actually, negate in the R code above, is also a kind of variable, albeit a special kind of variable: A function input argument which is local to the str_detect() function – i.e. it only exists inside of that function. It was named negate by the programmer of that function and we had no choice in the naming of it.

Think! What would happen if you created you own variable negate outside of the function str_detect()?

3 Literals

Unlike variables, literals refer to something which can not change during the course of the R code executing: they are determined by you, the programmer, at the time of writing and they remain constant when code is executed.

In the R code above, there are several literals: F, 35 and FALSE are all literals, but not the only ones. The F is a string literal and as such it is enclosed by quotation marks in the code: "F". The literal FALSE is special in that it is defined by R to have special meaning (logical FALSE as opposed to TRUE).

Think! What is the difference between the literal "2" and the literal 2? And what result do you think R will give you, if you try "2"+2?

4 Functions

Variables and literals both hold information. Functions, on the other hand, hold procedures, i.e. instructions about how to manipulate data (and do other cool stuff).

Base R contains many functions, e.g. mean(), sqrt() and read_csv(). Many more functions can be added through R packages. The function str_detect() above is from the stringr package, and not part of base R – i.e. we add it to R, only when we need it.

Typically, but not always, functions take one or more input arguments which serve as variables inside the function. Often, but not always, functions return data which can be stored in memory and referenced by a variable or passed to another function.

In the function str_detect() in the code above, we supply three arguments string, pattern and replace.

In the R code above, three functions are used: paste0(), c(), and str_detect().

Note how functions are always followed by a pair of brackets – you must include the brackets, even if no input arguments are passed as input to the function.

Think! What would happen if create a varible called c, given there is a base R function called c()?

5 Operators

Operators are really just a special way of writing a few specific functions with exactly two input arguments.

You could do multiplication as a regular function like multiplication(5, 4)1, but it would prove unwieldy. Instead, we use the conventional multiplication operator: 5*4.

The in-built base operators include *, +, ^,2 among others. R also includes logical operators like ==, !=, and <=3.

It is possible to create custom operators of the form %my_operator%. For example, %in% which is a logical operator used to test whether the left hand side (e.g a number) is present in the right hand side (e.g. a vector of numbers). 1 %in% 1:3 would yield TRUE. We do not recommend to create you own operators.

Take a look at this perfectly valid, albeit nasty R code:

sample <- str_split_1("sample", "")

sample <- sample(x=sample, size=length(sample))Can you identify the variables, the literals, the functions and the operators?

The word sample is used as both a variable, a literal and a function, but which is which?

- Variables

- The variable

sampleis referenced 4 times xandsizeare special variables: function input arguments

- The variable

- Literals

- Only two string literals are included in the code,

"sample"and""(empty string)

- Only two string literals are included in the code,

- Functions

str_split_1(),sample()andlength()are all functions – note, how the two string literals are passed as function input arguments to thestr_split_1()function without specifying the name of the arguments – this is okay, as long as they are listed in the correct order for the function.

- Operators

- Both the

<-and the=operators assign content from the right side to the left – it is convention to use<-to assign to common variables and=to assign to function input arguments, but they are actually interchangeable here.

- Both the

Bonus, what the two lines of code does, is to split "sample" in to the six constituent letters and mix them up, in random order.

6 Variabler, literaler, funktioner og operatorer

Det meste af den R-kode, du vil se på, består af:

- Variabler

- Literaler

- Funktioner (og operatorer)

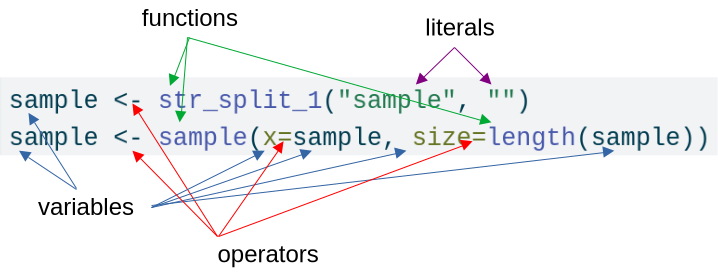

Det er meget nemmere at læse og forstå R-kode (og finde fejl), hvis du lærer at skelne disse fire elementer fra hinanden. Se på disse to linjer med simpel R-kode (bemærk, hvordan RStudio hjælper dig ved at anvende forskellige tekstfarver):

jet_airplane <- paste0("F", c(16, 35, 18))

x_is_in_string <- str_detect(string="my string", pattern="x", negate=FALSE) # str_detect will return FALSEHurtig forklaring:

paste0()indsætter"F"og tre tal i en vektor, såjet_airplanebliver til"F16" "F35" "F18". Funktionenstr_detect()lede efter mønsteret ("x") i strengen ("my string"), såx_is_in_stringbliver tilFALSE(i modsætning tilTRUE).

I det følgende over-simplificerer vi tingene lidt. For flere detaljer, vend senere tilbage til underafsnittet Self study / Core Concepts / Variables. Men her-og-nu: læs videre her for at lære at læse kode med variabler, literaler og funktioner:

7 Variabler

Variabler er navngivne referencer til data i hukommelsen. Du kan ikke arbejde med data i hukommelsen, på anden måde end gennem navngivne referencer, dvs. variabler.

På en måde minder dette om den måde, du bruger filnavne til at referere til individuelle filer på din computer: navnet forbliver det samme, selvom indholdet ændres.

I R-koden ovenfor er jet_airplane en variabel. Vi besluttede at navngive variablen jet_airplane på tidspunktet hvor vi skrev denne tekst – vi kunne have kaldt den (næsten) hvad som helst andet. x_is_in_string var også et skønsmæssigt valg af variabelnavn.

Faktisk er negate i R-koden ovenfor også en slags variabel, omend en særlig type variabel: Et funktions input argument, der er lokalt for str_detect()-funktionen – dvs. det findes kun inde i den funktion. Det blev navngivet negate af programmøren af den funktion, og vi havde intet valg i navngivningen af det.

Tænk! Hvad ville der ske, hvis du oprettede din egen variabel negate uden for funktionen str_detect()?

8 Literaler

I modsætning til variabler refererer literaler til noget, der ikke ændrer sig under R-kodeudførelsen: de bestemmes af programmøren på skrivetidspunktet, og de forbliver konstante, når koden udføres.

I ovenstående R-kode er der flere literaler: F, 35 og FALSE er alle literaler, men ikke de eneste. F er en strengliteral, og som sådan er den omgivet af anførselstegn i koden: "F". Literalen FALSE er speciel, idet den er defineret af R til at have en særlig betydning (logisk FALSE i modsætning til TRUE).

Tænk! Hvad er forskellen mellem literalen "2" og literalen 2? Og hvilket resultat ville R give dig hvis du prøvede "2"+2?

9 Funktioner

Både variabler og literaler indeholder information. Funktioner indeholder derimod procedurer, dvs. instruktioner om, hvordan man manipulerer data (og laver andre seje ting).

Base R indeholder mange funktioner, f.eks. mean(), sqrt() og read_csv(). Mange yderligere funktioner kan tilføjes via R packages. Funktionen str_detect() ovenfor er fra stringr-pakken og er ikke en del af base R – dvs. vi tilføjer den kun til R, når vi har brug for den.

Typisk, men ikke altid, tager funktioner et eller flere input-argumenter, der fungerer som variabler inde i funktionen. Ofte, men ikke altid, returnerer funktioner data, der kan gemmes i hukommelsen og refereres til af en variabel eller videregives til en anden funktion.

I funktionen str_detect() i koden ovenfor er der flere argumenter: string, pattern og replace.

I R-koden ovenfor bruges tre funktioner: paste0(), c() og str_detect().

Bemærk, hvordan funktioner altid efterfølges af et par parenteser – du skal altid tilføje paranteserne ved et funktionskald, også selvom der ikke sendes input-argumenter som input til funktionen.

Tænk! Hvad ville der ske, hvis man oprettede en variabel kaldet c, givet at der er en basis R-funktion kaldet c()?

10 Operatorer

Operatorer er egentlig bare en speciel måde at skrive nogle særligt udvalgte funktioner med præcis to input-argumenter.

Du kunne udføre multiplikation som en almindelig funktion som multiplication(5, 4)4, men det ville hurtigt vise sig at være uhåndterligt. I stedet bruger vi den konventionelle multiplikations-operator: 5*4.

De indbyggede basisoperatorer inkluderer *, +, ^,5 blandt andre. R inkluderer også logiske operatorer som ==, != og <=6,

Det er muligt at oprette brugerdefinerede operatorer af formen %my_operator%. For eksempel %in%, som er en logisk operator, der bruges til at teste, om venstre side (f.eks. et tal) er til stede i højre side (f.eks. en vektor af tal). 1 %in% 1:3 ville give TRUE. Vi anbefaler ikke at oprette brugerdefinerede operatorer.

Se på denne helt gyldige, omend ubehagelige R-kode:

sample <- str_split_1("sample", "")

sample <- sample(x=sample, size=length(sample))Kan du identificere variablerne, literalerne, funktionerne og operatorerne?

Ordet sample bruges både som en variabel, en literal og en funktion, men hvilken er hvilken?

- Variabler

- Variablen

samplebruges 4 gange xogsizeer specielle variabler: funktionens inputargumenter

- Variablen

- Literaler

- Kun to strengliteraler er inkluderet i koden,

"sample"og""(tom streng)

- Kun to strengliteraler er inkluderet i koden,

- Funktioner

str_split_1(),sample()oglength()er alle funktioner – bemærk, hvordan de to strengliteraler sendes som funktionens inputargumenter tilstr_split_1()-funktionen uden at angive navnet på argumenterne – dette er okay, så længe de er angivet i den korrekte rækkefølge for funktionen.

- Operatorer

- Både

<-og=operatorerne tildeler indhold fra højre side til venstre – det er konvention at bruge<-til at tildele til almindelige variabler og=til at tildele til funktions inpuargumenter, men de er faktisk omskiftelige her.

- Både

Bonus, hvad de to kodelinjer gør, er at opdele "sample" i de seks bogstaver og blande dem i tilfældig rækkefølge.

Footnotes

The function

multiplication()does not actually exist in R↩︎Multiplication, addition and exponentiation↩︎

Equal, not-equal and less-than-or-equal-to↩︎

Funktionen

multiplication()findes faktisk ikke i R↩︎Multiplikation, addition og eksponentiering↩︎

Lig med, ikke lig med og mindre end eller lig med↩︎